So…Networks came, Networks went…it ended up not being the best match for me this term…but there is always next year!

Alas…not this term.

16 Monday May 2016

16 Monday May 2016

So…Networks came, Networks went…it ended up not being the best match for me this term…but there is always next year!

28 Thursday Jan 2016

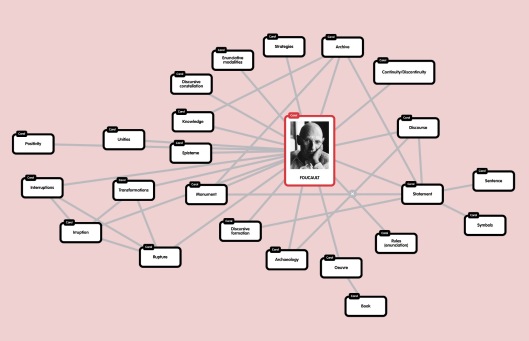

Foucault Mindmap-Popplet

26 Tuesday Jan 2016

Tags

archaeology, archaeology of knowledge, archive, discontinuity, discourse, discursive, displacements, ENG 894, foucault, interconnexion, irruption, oeuvre, preconceptual, reading notes, statements, structuralism, theory, transformations, unities

On my first pass, these are extensive summary notes as I needed them to try to be able to make any future sense of Foucault for application or understanding…I have some notes to myself to come back to along the way — but wow…Foucault, you made my brain hurt!

Archaeology of Knowledge – Michel Foucault

Archaeology of Knowledge – Michel Foucault

This book has been cited 21,525 times according to Google Scholar. That may be one of the largest I have seen. I note these things as I teach about the scholarly conversation and since coming back to school, I have noticed Foucault. A lot. Everywhere. In fact, to the point where I add a hashtag #foucaultiseverywhere with a photo tag to my FB posts as I see references. So this term seeing Archaeology of Knowledge on the syllabus was both exciting and terrifying.

How should I approach the book? Background reading first? Summaries so I don’t miss anything important? I chose overviews, along with my reading, trying to stop at each chapter to get the gist – but knowing as I got deeper into the book that full gists were not going to be possible on a first read, so vague ideas might be a better approach…

Oh yeah, don’t forget to apply to my OoS “First-Year Seminars”. . . so here it goes. First, summary notes so that I have reference points to come back to —

Part I – Introduction: Foucault points out that the study of history in the traditional way is being replaced by disciplines that look at histories of ideas, thought, science, literature and philosophy where they “evade very largely the work and methods of the historian” where “attention has been turned, on the contrary, away from vast unities like ‘periods’ or ‘centuries’ to the phenomena of rupture, of discontinuity” (4).

He sees history studied traditionally as a focus on “linear successions” — that study of “long periods” that attempt to

“reveal the stable, almost indestructible systems of checks and balances, the irreversible processes, the constant readjustments, the underlying tendencies that gather force, and are then suddenly reversed after centuries of continuity, the movements of accumulation and slow saturation, the great silent, motionless bases that traditional history has covered with a thick layer of event.” (3)

So, rather than continuities that look for patterns, it is the “interplay of transmissions, resumptions, disappearances, and repetitions” that become the points of study (5). BUT – he stresses that it isn’t one type of focus over another, “that these two great forms of description [continuities and discontinuities] have crossed without recognizing one another” (6) – because the problems are still on “the questioning of the document” (6). Instead of looking for the continuities – the interpretation that provides the truth, there is a push to “work on it [the document/text] from within and to develop it”:

“history now organizes the document, divides it up, distributes it, orders it, arranges it in levels, establishes series, distinguishes between what is relevant and what is not, discovers elements, defines unities, describes relations.” (6-7)

“history, in its traditional form, undertook to ‘memorize’ the monuments of the past, transform them into documents, and lend speech to those traces which, in themselves, are often not verbal, or which say in silence something other than what they actually say; in our time, history is that which transforms documents into monuments. In that area where, in the past, history deciphered the traces left by men, it now deploys a mass of elements that have to be grouped, made relevant, placed in relation to one another to form totalities.” (7)

Foucault attempts to clarify his aims in the Introduction. He writes he is not trying to put a “structuralist method” on the study of history or “use the categories of cultural totalities” to impose “forms of structural analysis.” Instead, he is posing ways to “question teleologies and totalizations” and “freed from the anthropological theme” look to “historical possibility” (16).

Paul Michel Foucault (1926-1984), philosophe français, chez lui. Paris, avril 1984. Credits: http://thissideofsunday.blogspot.com/2013/06/readings-in-race-drama-of-race-foucault.html

Part II -The Discursive Regularities:

It’s time to rid ourselves of the negatives says Foucault – get rid of the “mass of notions” that “diversifies the theme of continuity” that include tradition, influence, development, evolution and spirit, major types of discourse and most of all – the unities of the book and the oeuvre (20-22).

Foucault sees the need for a theory, one that “must be ready to receive every moment of discourse in its sudden irruption” (25). But – what is the purpose he asks for such a theory that breaks down the established unities? IT is the statement – with discourse as a way to analyze the statement. Discourse then becomes the OoS looking at the things said, and the statement without collective memory.

Knowledge archive – becomes another discursive effect rethinking what they are/do. If we start with the unities, but not from within them, then the forms of continuity can be suspended and the field set free (26).

Instead of chains of influence or tables of difference, look to systems of dispersion.

“Rather than seeking the permanence of themes, images, and opinions through time, rather than retracing the dialectic of their conflicts in order to individualize groups of statements, could one not rather mark out the dispersion of the points of choice, and define prior to any option, to any thematic preference, a field of strategic possibilities?”(37)

Foucault next sets out “rules of formation” for how his theory could be approached. He lays out three “rules” for how objects might have appeared as objects of discourse (40):

But – Foucault grows on me as he is constantly questioning himself – as he notes from the above, that “such a description is still in itself inadequate” (42) — as

“the problem is how to decide what made them possible, and how these ‘discoveries’ could lead to others that took them up, rectified them, modified them, or even disproved them.” (43)

He offers remarks and consequences for his proposed theory:

Conditions for saying things about an object – the same or different “are many are imposing” – and my favorite point of all –

“is it not easy to say something new; it is not enough for us to open our eyes, to pay attention or to be aware, for new objects suddenly to light up and emerge out of the ground” (43-44).

He gets it! New knowledge, finding new things to say – it is TOUGH! Thank you Foucault for recognizing this.

Objects exist “under the positive conditions of a complex group of relations” and they are “not present in the object” – broken down into primary (real) and secondary (reflexive) relations – with the secondary formed through discourse – and a system of relations (discursive) (45).

“Discursive relations are not . . . internal to discourse” – nor are they “exterior to discourse” – they are “at the limit of discourse” (46). They characterize “discourse itself as a practice” (46). Foucault stresses that “it is not the objects that remain constant . . . but the relation between the surfaces on which they appear” (47). Discourse then offers not a way to analyze an object, but a way for it to emerge through its own complexity (47).

This limit area that Foucault discusses makes me wonder how much it might be applied to liminal spaces – or boundaries, such as threshold crossings? [Note for follow-up to see if it comes up in areas of transfer, threshold or liminiality – as all of these are relevant in first-year and information literacy studies].

“what we are concerned with here is not to neutralize discourse, to make it the sign of something else . . . but on the contrary to maintain it in its consistency, to make it emerge in its own complexity. What, in short, we wish to do is to dispense with ‘things’. To ‘depresentify’ them. To conjure up their rich, heavy, immediate plenitude, which we usually regard as the primitive law of a discourse that has become divorced from it through error, oblivion, illusion, ignorance, or the inertia of beliefs and traditions, or even the perhaps unconscious desire not to see and not to speak. To substitute for the enigmatic treasure of ‘things’ anterior to discourse, the regular formation of objects that emerge only in discourse.” (47-48)

Analyze discourses – comes from ordering of objects – not treating discourses as “groups of signs” – but – “as practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (49).

Foucault asks the questions:

Arrangement of the statements governing things (57-58):

The procedures of intervention aren’t the same for all – there is a preconceptual level – anonymous dispersion through texts, books, oeuvres – “compatibility of differently opposed systems” (61).

Important to look at how the theories and themes — the strategies are distributed in history – was is successive or chance? Was there regularity? (64)

Foucault points to the direction of his research (65) through his previous writing, establishing his methodology for why he did/didn’t write/explain things in his previous books. For this book, his research is to

Foucault does not see an ideal discourse or “natural taxonomy that has been exact” — stressing that “one must not relate the formation for theoretical choices either to a fundamental project or to the secondary play of opinions (70).

His section of “Remarks and Consequences” (71) was like a breather chapter where he asks the questions of his own writing, trying to explain his whys, and provide counter interpretations. He asks if his work is worth it?

Interesting note from this chapter – Foucault points out the levels aren’t free from each other, but they are established in a reverse direction – with the lower not dependent on those above – there is coexistence, but not then co-reliance it would seem (73)? Choices and change stood out for me here, as discourse and systems produce each other – with the concept of boundaries coming up again here as well as a “regularity of a practice” (74).

Part III – The Statement and the Archive:

Foucault asks what has been his purpose – he does ask that throughout, as I imagine I can’t be the only one that had to keep flipping around in my notes thinking – what? He acknowledges he may have changed his points, or even his focus throughout, but that it is time to “take up the definition of the statement at its very root” – — starting to connect his descriptions.

So … what is a statement?

That then moves into “what is a sentence?” Are a statement and a sentence equivalent? Foucault says no, despite that “it is difficult to see how one is to recognize sentences that are not statements, or statements that are not sentences” (82). Finally – there is no “structural criteria of unity for a statement” – as it is “not a unit, but a function” (87).

Series of signs become a statement – if they possess “something else.” The relation between the signifier (significant) – to the signified (signifie) — “the name to what it designates” – or “the relation of the sentence to its meaning” – and the “relation of the proposition to its reference (referent) (89). And yet – the statement is not “superposable on any of these relations” — ACK!

And this – “A sentence cannot be non-significant; it refers to something, by virtue of the fact that it is a statement” (90).

Rule of repeatable materiality – example of different editions or printing of a book — but “small differences” not enough to “alter the identity of the statement” (102).

In defining statements – Foucault sees he has to draw from enunciative functions that bear on different units (106). There is a performance aspect to the statement

Foucault again begins to discuss what it seems he is doing –

I am trying to show how a domain can be organized, without flaw, without contradiction, without internal arbitrariness, in which statements, their principle of grouping, the great historical unities that they may form, and the methods that make it possible to describe them are all brought into question. (114)

Rather than founding a theory – and perhaps before being able to do so (I do not deny that I regret not yet having succeeded in doing so) – my present concern is to establish a possibility. (115)

Thus, he lays out a number of propositions about discursive formations (116-117) that establish the need for them to be justifiable and reversible, as part of discursive practice.

Foucault places discourses between the “twin poles of totality and plethora” (118).

Discourse

Foucault points out that “Our task is not to give voice to the silence that surrounds them, nor to rediscover all that, in them and beside them, had remained silent or had been reduced to silence” (119) – so to what extent is this in contrast to Derrida and making meaning in the void – that blank space between the columns? For Foucault, exclusions are not being linked to repression. His focus in on the said, the spoken – the enunciative domain – that which is on the surface – “to interpret is a way of reacint to enunciative poverty” (120)

To describe a group of statements not as the closed, plethoric totality of a meaning, but as an incomplete, fragmented figure; to describe a group of statements not with reference to the interiority of an intention, a thought, or a subject, but in accordance with the dispersion of an exteriority; to describe a group of statements, in order to rediscover not the moment or the trace of their origin, but the specific forms of an accumulation, is certainly not to uncover an interpretation, to discover a foundation, or to free constituent acts; nor is it to decide on a rationality, or to embrace a teleology. It is to establish what I am quite willing to call a positivity. (125)

Positivity has a role in historical a priori – which “take[s] account of the fact that discourse has not only a meaning or a truth, but a history, and a specific history that does not refer it back to the laws of an alien development” (127).

The archives are then those “systems of statement” articulated through historical a priori (events or things)

The archive is first the law of what can be said, the system that governs the appearance of statements as unique events. But the archive is also that which determines that all these things said do not accumulate endlessly in an amorphous mass, nor are they inscribed in an unbroken linearity, nor do they disappear at the mercy of chance external accidents; but they are grouped together in distinct figures, composed together in accordance with multiple relations, maintained or blurred in accordance with specific regularities; that which determines that they do not withdraw at the same pace in time, but shine, as it were, like stars, some that seem close to us shining brightly from afar off, while others that are in fact close to us are already growing pale. (129)

An archive is not the “library of all libraries” – “it is the general system of the formation and transformation of statements” (130).

Part IV – Archaeological Description:

So…what to do? Foucault starts this part with a note that this thing he calls archaeology – “are at the moment . . . rather disturbing” (135)

While he writes that he set out with “a relatively simple problem” (yeah right…), he has gotten out of hand as he has moved into a “whole series of notions” that

“I have tried to reveal the specificity of a method that is neither formalizing nor interpretative; in short, I have appealed to a whole apparatus, whose sheer weight and , no doubt, somewhat bizarre machinery are a source of embarrassment.” (135)

And he asks, are more methods needed? Is it “presumptuous” to want to add another? He has a “suspicion” that while he has tried to avoid drawing from the history of ideas, has he “all the time” been in that very space?

“Perhaps I am a historian of ideas after all. But an ashamed, or, if you prefer, a presumptuous historian of ideas. One who set out to renew his discipline from top to bottom; who wanted, no doubt, to achieve a rigour that so many other, similar descriptions have recently acquired; but who, unable to modify in any real way that old form of analysis . . . declares that he had been doing, and wanted to do, something quite different. All this new fog just to hide what remained in the same landscape, fixed to an old patch of ground cultivated to the point of exhaustion.” (136)

But he presses on – as he writes he won’t be satisfied until he has “cut myself off” from the history of ideas and “shown in what way archaeology differs” (136).

This was an interesting section, as one of the classes I teach looks at the history of ideas, especially related to technology and how knowledge/scholarship has developed. Foucault recognizes the necessity for crossing disciplines and sees the “history of ideas . . . [as a] discipline of beginnings and ends, the description of obscure continuities and returns, the reconstitution of developments in the linear form of history” (137). It can also be seen as the “discipline of interferences” or of “concentric circles.”

So, what is the difference from his archaeology? He sees “a great many points of divergence,” but four discrete differences:

In his approach, Foucault is attempting to open up future exploration – distinguishing between linguistic analogy and enunciative homogeneity –uncovering the regularity of a discursive practice. This is what archaeology is interested in – the emergence of disconnexions.

In looking for the smallest “point of rupture” – between the already said and the “vivacity of creation” into differences – there are two methodological problems: resemblance and procession (143).

Archaeology is looking to establish the “regularity of statements” as “every statement bears a certain regularity and it cannot be dissociated from it” (144). It is not in “search of inventions” or “concerned with the average phenomena of opinion” – but rather the enunciative regularities of statements.

Archaeology is concerned with and only with – the homogeneities of linguistic analogy, logical identity and enunciative homogeneity (145) and one of its principal themes — “may thus constitute the tree of derivation of a discourse” (147) with governing statements at its root.

“Contradictions” [Part IV, Chapter 3] pokes at coherence – and the contradictions that arise within the history of ideas’ use of it, pointing to the need for analysis to “suppress contradiction as best it can” (150). He looks for his own contradictions in this work, asking if there are only minimal ones at the end, or if there is a “fundamental contradiction” that might emerge that might constitute “the very law of its existence” – as it is on this that discourse emerges – as the “contradictions…function throughout discourse, as the principle of its historicity” (151).

“Discourse is the path from one contradiction to another” (151)

And in this chapter I found my AHA moment here

Archaeology is looking at how the contradictions derive from a certain domain – that fundamental level that “reveals the place where the two branches of the alternative join” — “where the two discourses are juxtaposed” — “to determine the extent and form of the gap that separates them.” Archaeology “describes the different spaces of dissension.” (152)

“Archaeology, however, seems to treat history only to freeze it” (166).

For an archaeological history of discourse – two models must be put aside –

Instead of homogenous events that make up discourse, archaeology looks at the levels of statements themselves, their derivation, or unique emergence (170), the changes/transformations that occurred.

Responding to perceived questions that might come up, Foucault points out that

In the section “Different thresholds and their chronology” – this furthers my idea that there are connections to the threshold concepts – post Foucault, as well as liminal spaces – while those terms are never used here – he does forward thresholds – of positivity, epistemologization, and formalization. For Foucault, he notes they are domains for further exploration. He is pushing against a linear movement or passing through for any of these thresholds and (186 187). [Come back to these points for case study to align with FYS and IL].

Archaeology is concerned with not describing specific aspects of science, but “the very different domain of knowledge” (195).

Part V – Conclusion:

Referring to himself as “you” in the beginning of conclusion as if to speak from the audience’s response to his text – Foucault points to the “great pains” he took to “disassociate” himself “from structuralism,” echoing his original point from his Introduction (199). But here he asks, what was the benefit if he didn’t take advantage of the benefits of structural analysis? Moving back to I, he expands on his misunderstanding – of the “transcendence of discourse” and in refusing “to refer to it as a subjectivity” (200). The “you” and “I” banter continues in the conclusion – as if he is having a conversation with a critic.

He writes that he did not “deny history, but held in suspense the general, empty category of change in order to reveal transformations at different levels” (200). Foucault asks if the discourses he is following are philosophy or history (205)? He’s rather coy here – citing embarrassment in being found out – as if he wanted the suspense to continue – and to be able to draw from both – and “avoiding the ground on which it [his discourse theory] could find support. This is a “discourse about discourses” (205).

What came across throughout the book was that Foucault wasn’t trying to dictate a new way to think or to respond to history. In fact, he provides commentary on his own self-doubt as to what he is doing in different parts of the text, such as the “impotence of his method” (199). He is questioning, offering alternatives and putting it all out there for discussion . . . which at the end was much more appealing for how I might start to think about my own OoS and trying on new theories. They might work, they might not, but that’s ok. Thank you Foucault!

Connections and Thoughts: Too early…that is my first impression – as I read back through my notes after reading the text, writing the notes, reviewing what’s been said about the text and still – my brain hurts and I’m not sure I even see a “theory” in all of this to compare.

As I start to think about my OoS: FYS and how they tie into networks, the amount of interaction they have with the various constituents on campus – from the disciplinary faculty to the library to the writing, speech and academic skills centers, to CAPS and Civic Engagement, it’s begging for a Popplet of its own [coming soon] that I can then link out to the theories and readings that I will be starting to put together.

For this week, Foucault’s questioning and approach to history [and discourse] drew out some interesting terms I noted throughout – especially as he stressed the discontinuities and transformational offerings that looking at history – or any subject through this different lens might offer new understandings. I admit, I think linearly and when I’m asked to go outside this comfort area to visual approaches, I want to apply my linear way of thinking to a visual medium. When Foucault writes that moving away from linear ways of thinking is his approach, it is intriguing as he isn’t offering visual in its stead, but rather ruptures and a move back to preconceptual understanding and its irruptions (I hadn’t seen that work before, but I like it!).

Photo and Quote from http://sites.psu.edu/foucault2016/2016/01/

Works Cited and Bibliography

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge & the Discourse on Language. Trans. From the French by A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Pantheon Books, 1972.

Gutting, Gary, “Michel Foucault”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.).

24 Sunday Jan 2016

Rhetorical Situation – Mindmap #1

Rhetorical Situation – Mindmap #1

22 Friday Jan 2016

Tags

composition, dissertation, faculty, first year experience, FYS, networks, OoS, proposal, research, university, WAC, WID, writing

My object of study is the First-Year Seminar (FYS). There are two types of typical first-year course offerings in colleges and universities: the first-year experience (FYE) course that is focused on social acclimatization of students that may or may not be required and the first-year seminar, a content-rich course that is required as part of the academic curriculum and is taken either in conjunction with or in lieu of an alternate freshman writing sequence. Both types of programs stress ways to improve the transition from high school and first-year experience for students through developing the holistic person, academically, socially, and through a combination of initiatives. These efforts encourage early bonding between students and professors in small group settings using common readings or themes of courses, often included under efforts to improve first-year retention with a larger first-year experience (FYE) setting. The National Resource Center for First-Year Experience and Students in Transition is one of the main research/resource sites. They point in their history to an over 35 year trajectory of work stemming from their initial University 101 concept to first-year seminars now required as part of a college or university’s curriculum across the United States.

This object of study is important to English studies, specifically writing studies because it is increasingly being offered as an alternative to a composition or writing sequence for freshmen, taught by faculty from across the curriculum in many cases, but who are expected to teach a range of foundational skills, historically aligned with a FYW curriculum. How FYS are being planned, taught and supported across an academic institution has the potential to impact curriculum, especially within Writing Studies. Within my own institution, we have had a FYS program for five years and the combined expectations on faculty across the disciplines for teaching critical thinking, reading, writing, and research skills remains challenging to support and maintain.

It is instructive to think of the multi-faceted ways that FY Seminars could be viewed and studied as a network. As integral courses within the curriculum, they have the potential to connect faculty from across campus, as well as a range of campus partners and support units that may/may not include teaching faculty (such as the writing, academic skills or speech centers, civic engagement, libraries, or technology). As a cross-disciplinary, university-wide program the classes can impact all facets of student learning, through teaching for and encouraging transfer of skills/knowledge, relationship building, and introduction to the academic enterprise. FYS can offer support to students by including faculty as mentors, building awareness of campus resources or bonding between students in small and intensive discussion-based classes centered on a learning community approach. When successful, FYS can provide a multi-faceted, integral and inclusive initiative to foster community within a campus. But, if not fully integrated into a university’s culture, curriculum and fabric, they offer the potential to alienate faculty, underserve students and become a burden to administer and retain.

For my dissertation research, I want to focus on faculty in the disciplines who teach writing within a first-year seminar, but for the purposes of this class, as you talked through Writing Centers with Kim during class, I saw benefit by starting with a broader approach, that of the first-year content seminar and how it does/could operate as a network on a campus through the above mentioned ways. My question is to what extent should I specifically bring in the teaching of writing or is it ok to start with the broader FYS concept, gain a deeper understanding and knowledge-base within FYS scholarship, then develop the faculty writing WAC and WID as applied to FYS through my continuing research outside this class?

Representative image of my object of study.

Object of Study – FYS – Representation Image

Working Bibliography

Brent, Doug. “Using an Academic-Content Seminar to Engage Students with the Culture of Research.” Journal of the First-Year Experience & Students in Transition 18 (2006): 29-60.

Chapman, David W. “WAC and the First-Year Writing Course: Selling Ourselves Short.” Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication, 1997.

Connors, Robert J. “The Abolition Debate in Composition: A Short History.” Composition in the Twenty-First Century: Crisis and Change. Eds. Lynn Z. Bloom, Donald A. Daiker, and Edward M. White. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois UP, 1996. 47-63.

Daniell, Beth. “FY-Comp, FY-Seminars, and WAC: A Response.” Language and Learning Across the Disciplines 2 (1998): 69-74.

Fernandez, Nancy Page, Sally Murphy, Jennifer Keup, and Ken O’Donnell. Intellectual Oomph in the First-Year Experience.

Keup, Jennifer. National Research and Trends on High Impact Practices in the First-Year Seminar.

Skipper, Tracy. First-Year Seminars and Senior Capstones: Bookending Writing Instruction and the Undergraduate Curriculum.

—. Writing in the First-Year Seminar: A National Snapshot.

Teymuroglu, Zeynep. “Service-Learning Project in a First-Year Seminar: A Social Network Analysis. Primus : Problems, Resources, and Issues in Mathematics Undergraduate Studies, 23.10 (2014): 893-905.

Young, Dallin George, and Jessica M. Hopp. 2012-2013 National Survey of First-Year Seminars: Exploring High-Impact Practices in the First College Year.

18 Monday Jan 2016

Tags

activities, computers, ENG 894, holographs, long-term memory, memory, networks, short-term memory

Computer Memory Pyramid from http://computer.howstuffworks.com/computer-memory-pictures.htm

Memory as related to computer technology is what gives the computer storage and retrieval capability. It can be part of the computer’s hardware or as a removable storage device. See Week 1’s Reading Notes for additional details as to types of memory and comparisons of computer to human memory.

Key Terms/Definitions:

Holographic Memory from http://computer.howstuffworks.com/holographic-memory.htm

Understanding computer memory is a part of an overall understanding of how the parts of an item fit into the larger object and become part of the structure of the larger entity. In the case of computer memory, it is essential in how information is stored and retrieved. While there are a myriad of types of memory for computers, from temporary, quick-access memory that is used as a form of exchange to allow for quicker running of programs and operations, there is also long-term memory or storage that provides pathways for retrieval of information at a later time. Stopping to think about how the pieces fit together and are part of a larger network, whether parts of a whole or parts of a larger system cause me to think differently about what surround my daily life. How are networks part of the world beyond just computers?

The memory and larger computer as object operate as part of a network as very few are not somehow hooked to other computers, printers, peripheral devices or larger computer systems or networks. Without Internet connectivity, a computer may operate as its own network, through its internal pieces, but it is the connectivity to the larger network that opens up the real functionality of its operation possibilities. It is limited in its network options by the speed and connectivity options. For computer memory, this means how much memory does the computer have? What does it need to operate the necessary programs/activities of the user. This is not a singular item, as each program or operation uses computer memory differently and the needs are constantly changing. How much memory is enough? Some of the articles mentioned as much as you can afford – which brings in the attendant power aspect in that not everyone can afford the most or the best and so network limitations can too depend on $$ and who you are, as much as where you are.

Want More? Try the How Stuff Works – Computer Memory Quiz

How Stuff Works > Tech > Memory Bibliography

Bonsor, Kevin. “How Holographic Memory Will Work” 8 November 2000.

Crawford, Stephanie. “How Secure Digital Memory Cards Work” 17 October 2011.

Saha, Sarishti. “Holographic Digital Data Storage: A Fad or Here to Stay?” 15 June 2015. Yaabot.

Tyson , Jeff. “How Virtual Memory Works” 28 August 2000.

Tyson, Jeff, and Dave Coustan. “How RAM Works” 25 August 2000.

Tyson, Jeff. “How Computer Memory Works” 23 August 2000.

Tyson, Jeff. “How Flash Memory Works” 30 August 2000.

18 Monday Jan 2016

Tags

audience, biesecker, bitzer, brain, computers, connections, context, derrida, differance, latour, memory, networks, processing, rhetorical situation, rickert, situation, symbols, theory, vatz

The pre-week 1 readings all discussed the rhetorical situation, while providing differing views on the role and place of situation, context, and audience. I read the articles in chronological order, so as Lloyd Bitzer (1968) wrote of the nature of the rhetorical situation, with the necessity for situation to precede rhetorical discourse, his argument seemed logical. In order for there to be rhetorical discourse on an event or situation, it first must occur and is based on five general characteristics: it is provided as a “fitting response” prescribed by the situation, that is also located in reality, exhibits structures and provides a level of maturation in that it comes into existence, matures and then decays or persists.

For Bitzer, “rhetoric is situational” (3) as he defines it contains three constituents: exigence, audience and constraints and can be defined as

A complex of persons, events, objects, and relations presenting an actual or potential exigence which can be completely or partially removed if discourse, introduced into the situation, can so constrain human decision or action as to bring about the significant modification of the exigence. (6)

Rhetorical situations that persist become part of the body of rhetorical literature – those universal rhetorical situations, such as the Gettysburg Address, MLK’s “I Have a Dream” or Socrates’ Apology. In Bitzer’s view, meaning is always intrinsic to the rhetorical situation, situations must be persuasive and they must answer an urgent need.

Richard Vatz provides a response to Bitzer, pointing to what he calls the “myth” of the rhetorical situation. According to Vatz, Bitzer misses key aspects, that of the quality of the situation, the relationship between the rhetor and the situation, and the role of choice as a necessity for how a situation is communicated. For Vatz, there is no static individualized situation, instead rhetorical discourse is a form of translation of choices, communicating select aspects of situations, not a situation. Proposing an alternate to Bitzer, Vatz outlines how situations are rhetorical and utterances are what invite exigence. For Vatz, rhetoric is a cause, not an effect of meaning as no situation can be independent of the perception of the interpreter.

Vatz’ “essential question” is what is the relationship between rhetoric and situations (158) with Bitzer and Vatz offering opposite views. Vatz sees political motive in some rhetorical situations, with them being “created” rather than “found” (159), such as the case of the “Cuban Missile Crisis” as it was both an act of rhetorical creation, as well as a political crisis. This resonated with me having just finished a class in Cultural Affect and the ways that emotions can often be “sold” to a populace through the media or via authority, as a “culture of fear” or a “war on terrorism” can become part of a society’s fiber of action/response, as Vatz notes that rhetoric can “create fears and threat perception” whereby speeches are needed to “communicate reassurances” (160).

Barbara Biesecker offers a different position surrounding rhetorical situation, while drawing from Vatz and Bitzer, but counters the historical “exchange of influence” aspect of the rhetorical situation, focused on speaker and audience. Biesecker writes that a “rethinking “ is necessary as only seeing discourse as situation-exigence through influence or its “historical character,” or even through an “exchange between individuals” tied to an event is limiting. By reexamining symbolic action (the text) and subject (audience) using Derrida’s Différance, the rhetorical situation can be rethought as articulation. Through a lens of deconstruction, the “rhetoricity of all texts [can be taken] seriously” (111) by offering “a way of reading that seeks to come to terms with the way in which the language of any given text signifies the complicated attempt to form a unity out of a division” (112).

For Biesecker, audience is a part of the rhetorical situation as an “effect of différance and not the realization of identities” providing governance by a “logic of articulation” over influence. Rather than see situation or speaker as the point of origin and thereby forcing a who is right or wrong, viewed through différance, that “division within as well as between distinct elements” (115) can focus instead on the interrelatedness of signs

…this interweaving, this textile, is the text produced only in the transformation of another text. Nothing, neither among the elements nor within the system, is anywhere ever simply present or absent. There are only, everywhere, differences and traces of traces. (Derrida, “Semiology and Grammatology,” Positions, 26).

Through the middle spaces, those that may be considered voids – the folds, are the places where meaning can be made. This stress on avoiding dichotomies or binaries also for me, is reflective of later affect and critical theory, as layered understandings and recognizing multiple voices and narratives replaces a strict hierarchy of either/or interpretations. In looking at a text from reception instead of production, the audience, while always a part of the rhetorical situation, often “receives little critical attention . . . simply named, identified as the target of discursive practice, and then dropped” (122). Audience within différance is viewed as an aspect of production or effect-structure (125). As the subject is destabilized, then the rhetoric becomes shifting and uncentered, constructing and reconstructing the linkages (126).

Biesecker’s article will take more time and application for me to really see its potentiality. Thinking about rhetorical situations through difference caught my interest as I like the idea of making meaning in the middle, rather than being directed by situation, but my understanding as she delved deeper into articulation remains a bit murky.

Thomas Rickert’s article draws from Bruno Latour, another new theorist for me, so as with Derrida and différance, on first read, clarity was not offering itself up. Rickert uses the example of wine tasting to illustrate how context can be elevated over the object, based on perceptions of what is thought about the object over the actual properties of the object itself. Latour, Rickert points out is critical of context, as he would rather look at the “things and objects—that make up an assembled entity” (135). Rickert applies Latour in looking at how context (what he notes is irrepressible) emerges “as an assemblage of complexly interactive variables (or actants)” (136). Latour uses dingpolitik— a politic of things—as he points to politics as rhetorical, with the social as “inseparable from its material infrastructure” (136). Rickert recognizes the benefits of Latour’s approach, but also points out its shortcomings, such as assemblage and how persuasion comes into play, as well as context, looked at as a “holistic notion of the ‘as a whole’” (137). Rickert argues that “context retains its holistic dimension but that this scope is neither stable nor the sole result of human doing” (137). Latour stresses writing and describing over context, but Rickert questions Latour’s criticism of context, viewing it instead as both a boundary and an element (141), rethinking context as “having a dual role” within two dimensions of 1) a holistic, material ecology; and 2) the relation of relations that looks at the “howness” of things.

Comparisons:

| Bitzer | Vatz | Biesecker (Derrida) | Rickert (Latour) |

| Rhetoric is situational | Situations are rhetorical | Articulation over influence | Objects become rhetorical as they are inseparable from what engage us |

| Exigence invites utterance | Utterances invite exigence | Rhetoricity in all texts through différance | Dingpolitik – politic of things. Persuasion achieved through an assembly of actants (136) |

| The situation controls the rhetorical response | The rhetoric controls the situational response | Différance makes signification possible | Latour critical of context / Rickert offers holism |

| Obtains its character as rhetoric from the situation which generates it | Situations obtain their character from the rhetoric which surrounds them | Différance is the nonfull, nonsimple “origin”; it is the structured and differing origin of differences (117) | Rickert – holistic aspect as “howness” of things through assemblage |

How Stuff Works is useful website as a reference tool. I tend to think of it as a technology information site, but in looking at its “About” page, it reflects a much broader range of how “the world” works – so definitely a source for me to remember as students are looking for quick and clear explanations.

Human and computer brain from http://www.techweekeurope.co.uk/workspace/university-building-human-brain-model-33719

My topic for reading is “Memory.” I first went into the main Memory topic, which focused on human memory and brain science. Once I went back and realized it was only the technology “Memory” section I was to read and comment on, I was actually glad to have read the others first, as I saw connections and a number of similarities in how both human memory and computer memory can be similar and also relate to teach other. Both can easily be viewed as networks – with the brain as part of the body’s network of organs, or even just within the brain, the network of thought and mind. Computers run on a network of individual pieces that come together to make things happen, but also are pieces of larger entities, as most home computers are now networked within a house, hooked to printers, each other, and the larger world through Internet connections. As I start to really think about the interactivity of how one piece of something interacts and affects the other pieces, the idea of assemblage (Rickert) and stepping away to see a holistic picture is intriguing.

Most gadgets in the 21st century have some form of memory. Memory can be either short or long-term, much like human memory. In a computer, it often refers to the amount of quick access storage available that includes RAM, virtual and caching. It is considered a form of temporary storage, but is one of the most important aspects in computer performance, especially for high graphics and gaming. As part of the “team” that runs a computer, it is a form of network, as it relies of the different parts to communicate, react and provides successful computing experience.

Computers can use both static and removable storage. ROM is a form of static storage, while floppy discs were the first removable storage. Today, storage can come from hard-drives, flash memory or light. Light has been a form of storing and reading data since compact disc (CD) technology—over thirty years ago. A CD Digital versatile disc (DVD) improved on this in the 1990s allowing for much greater density of storage.

Mapping Memory from http://designcanes.com/

Holographic memory storage is the newest form, poised to improve optical storage by enabling 3D volume storage that goes beyond the current surface storage on CDs or DVDs. For size comparison, 1 TB (terabyte) could be stored on a crystal the size of a sugar cube in holographic memory, the contents of 1,000 CDs. Form of storage was first discovered by Pieter van Heerden, a Poloroid scientist, in the 1960s. While early on touted as the next storage breakthrough, it has not become popular, despite continuing research and testing. Online tech blogger, Sarishti Saha writes, “[a]lthough the technology boasts of revolutionary changes in the data-storage industry, a few more than one Achilles’ heels have always let it down in the past endeavors. We could only hope that if it shows up next time, it stays in the market for keeps.”

For the human brain, memory is the process of bringing what is learned and retained into the conscious mind. It is measured in two ways: recall and recognition and classified though either short-term—quickly forgotten, insignificant items that may be forgotten in a few seconds, or long-term memory, important items that may last through years or a lifetime. Skills are identified as memories that utilize motor responses.

Remembering is more effective if a person cares about the subject, can apply it to what is already known, and learns in small chunks with frequent breaks and recall sessions. Mnemonics can be helpful in remembering, as well as familiar stimulus, such as identifying a place with a song or smell. Retroactive inhibition—items too similar to previous memories, repression—exclusion from the conscious due to conflict and distortion—false or changed perceptions based on a possibly traumatic event are all barriers to remembering. People are much more likely to remember events in detail that are emotionally disturbing, as emotion and memory are connected in the brain. Fear is part of the amygdala and is a key facet of core memories. While people may not remember good memories as well, their recall can be beneficial as they release dopamine, a “feel good” neurotransmitter.

While some people may find it easier to not be as affected by negative emotions, others seem to intensify the negative. Clinicians can help to teach techniques for better dealing with emotions, while there are also individual ways people can manage difficult memories, including relaxation, writing down feelings, or using positive imagery. Strengthening positive memory recall can be done by focusing on them while they are occurring or to think more about them after they are over.

Memory begins to decline with age, but there are ways to help retain and improve memory:

Types of unusual memory include eidetic (photographic), hypermnesia (exaggerated detail), and amnesia (complete loss or repressed) usually due to a trauma or emotional event. The cerebral cortex houses the higher level intellectual processes. Within this is the lateral area that contains the hippocampus (places and facts) and amygdala (emotions and skills) that retain different types of memories. Learning is dependent on synapses in the brain that are strengthened by glutamates—chemicals that activate NMDAs neurons to boost memory. Yet, exactly how memory works and in what capacity people remember is not fully understood.

In looking at connections between the readings, Rickert’s example showing people’s gullibility and the unreliability in ascertaining an object and quality within different contexts is also frequently applied to memory and how time and situation – dependent on the intensity of the situation can affect how people remember events.

Pre & Week 1 Readings

Biesecker, Barbara A. “Rethinking the Theoretical Situation from within the Thematic of ‘Différance.’” Philosophy & Rhetoric 22.2 (1989): 110-130.

Bitzer, Lloyd F. “The Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 1.1 (1968): 1-14.

Bonsor, Kevin. “How Holographic Memory Will Work” 8 November 2000. HowStuffWorks.com.

Cancio, Colleen. “Do we remember bad times better than good?” 4 October 2011. HowStuffWorks.com.

Crawford, Stephanie. “How Secure Digital Memory Cards Work” 17 October 2011. HowStuffWorks.com.

“Memory.” 05 October 2009. HowStuffWorks.com.

Rickert, Thomas. “The Whole of the Moon: Latour, Context, and the Problem of Holism.” [Ch. 8]. Thinking with Bruno Latour in Rhetoric and Composition. Eds. Paul Lynch and Nathaniel Rivers. Chicago: Southern Ill. UP, 2015. 1435-150.

Saha, Sarishti. “Holographic Digital Data Storage: A Fad or Here to Stay?” 15 June 2015. Yaabot.

Tyson , Jeff. “How Virtual Memory Works” 28 August 2000. HowStuffWorks.com.

Tyson, Jeff, and Dave Coustan. “How RAM Works” 25 August 2000. HowStuffWorks.com.

Tyson, Jeff. “How Computer Memory Works” 23 August 2000. HowStuffWorks.com.

Vann, Madeline Roberts. “5 Memory Boosters” 10 September 2008. HowStuffWorks.com.

Vatz, Richard E. “The Myth of the Rhetorical Situation.” Philosophy & Rhetoric 6.3 (1973): 154-161.